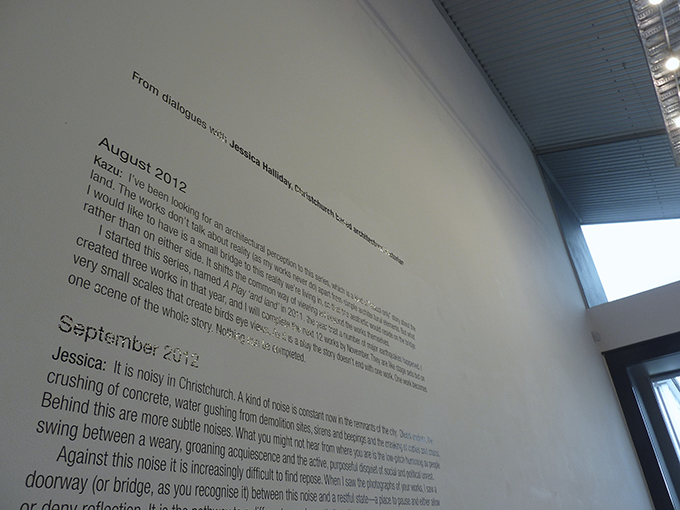

From dialogues with Jessica Halliday, Christchurch based architectural historian

August 2012

Kazu; I've been looking for an architectural perception to this series, which is a kind of "visual only" story about the land. The works don't talk about reality (as my works never do) apart from simple architectural elements. But what I would like to have is a small bridge to this reality we're living in, so that the aesthetic would reside on the bridge rather than on either side. It shifts the common way of viewing art beyond the works themselves.

I started this series, named A Play 'and land' in 2011, the year that a number of major earthquakes happened. I created three works in that year, and I will complete the next 12 works by November. They are like stage sets but on very small scales that create birds eye views. As it is a play the story doesn't end with one work. One work becomes one scene of the whole story. Nothing can be completed.

September

Jessica; It is noisy in Christchurch. A kind of noise is constant now in the remnants of the city. Diesel engines, the crushing of concrete, water gushing from demolition sites, sirens and beepings and the creaking of cables and chains. Behind this are more subtle noises. What you might not hear from where you are is the low-pitch humming as people swing between a weary, groaning acquiescence and the active, purposeful disquiet of social and political unrest.

Against this noise it is increasingly difficult to find repose. When I saw the photographs of your works, I saw a doorway (or bridge, as you recognise it) between this noise and a restful state - a place to pause and either allow or deny reflection. It is the pathway to a different sound, a path that allows the keening over loss to find voice, the necessary acknowledgement of grief. Without this mourning for our cultural loss, the destruction of the fabric of our city, it will be near impossible for many of us to find a way into the future.

Kazu; Yes, I can still hear the noise you talk about from a memory of my visit to your city last April. Although it was a weekend, I watched the huge crane with its drill trying to demolish a concrete column on the 8th or 9th floor that refused to be knocked down. The smell of the concrete dust from a distance reminded me, ironically, of my childhood. When the city of Tokyo was full of construction at every corner of every town, probably at its peak after WWII when the city was completely ruined by millions of iron raindrops from the sky. Twenty years later at the age of seven, I was running around a small corner of that city curious about everything I encountered. I put my tongue against a surface of a big building and licked the wall. It was the year of the Tokyo Olympics that my playground was turned into a forest of concrete. Which I of course loved - it was all I knew.

November

Jessica; The image of a child, so curious, so thrilled by the city growing and morphing around him that he tastes it, tests its texture with his tongue, is so hopeful, so beautiful. Such abandon, such lack of self-awareness—how do we cultivate that here now?

That period of architecture in Japan fascinates me—Kunio Mayekawa, Noboru Kawazoe, Kenzo Tange—the giants of Japanese post-war modernism. They saw reinforced concrete frame construction through the lens of Japanese timber traditions, sealing the idea that Japan had anticipated modern architecture. The lessons we can glean are many but they’re all built on the premise that it is important to establish a dialogue between the past and the present.

Kazu; In February this year, I, with my 18 year old son, visited Kesennuma city in Tohoku, one of the areas most devastated by the northeastern Japan earthquake and tsunami. Arriving at the small railway station and walking along the downtown street, it didn’t look a ruined city at all until we turned one corner where we saw a different world, a scene deleted from the land. A year had already passed since the ocean washed through the streets and buildings, and what we saw could tell us nothing about a moment that had changed daily life. It was, however, far more than

I could accept. We walked and walked for three days to see what we could see. On the morning we left, snow was falling. It covered the entire city making it utterly white overnight. I couldn’t stop thinking about a volume of human beings and a volume of nature.

at the exhibition foyer gallery